Tommy loved trains. He didn’t know why he loved trains and he’d never actually ridden on a train, but for all of his ten years he had lived across the river from the train tracks. Every night he’d slept hearing the sound of train whistles and he guessed that’s where his love of trains started. He gave this answer without expression every time he was asked and adults asked him this a lot, as if this was all that mattered about him. Usually adults would peer down at him invasively, squinting hard, like they might determine what his insides were saying by the way his outsides looked. His mother said it was because he was unusually quiet for a boy—she said he was “sucked into himself.” When she said this, he thought of sitting inside a huge pink bubblegum bubble, trapped and on display.

Tommy loved trains. He didn’t know why he loved trains and he’d never actually ridden on a train, but for all of his ten years he had lived across the river from the train tracks. Every night he’d slept hearing the sound of train whistles and he guessed that’s where his love of trains started. He gave this answer without expression every time he was asked and adults asked him this a lot, as if this was all that mattered about him. Usually adults would peer down at him invasively, squinting hard, like they might determine what his insides were saying by the way his outsides looked. His mother said it was because he was unusually quiet for a boy—she said he was “sucked into himself.” When she said this, he thought of sitting inside a huge pink bubblegum bubble, trapped and on display.

Already Tommy was tired of school, only 2 months into his fifth grade year. He was bored with the younger kids, in the cafeteria, in the halls, on the playground. He resented their squeaky voices, their little hands rubbing the walls, the tiny toilet in the bathroom reserved for them. Tommy longed for the freedom he imagined that middle school offered and felt dejected when he thought about it, realizing it was a full year away. He especially disliked having to be with the baby-kids on his school bus. They took forever to load and unload, skipping up their driveways, waving to their mothers, annoyingly pausing to pet their dog instead of crossing the street.

It was Tuesday, the fifth of September, that bleak time in the south when the summer is still in full heat-bloom and the next school-respite, Thanksgiving, was impossibly in the distant future. His was the last stop in the afternoon and the first stop in the morning. Most days, school exhausted him and the forty-five minute ride home lulled him into a half-asleep state. When the bus clattered across the train tracks before turning into the gravel, river-side parking that marked the end of his road, Tommy roused from his daze, swayed up the bus aisle between the empty seats and catapulted off the last step, twisting his ankle awkwardly in a deep crater, one of many littering the rough landing. He felt the familiar blast of dust and hot air against his back as the driver slammed the door. Standing on the edge of the gravel, pressed against the tall weeds, he watched as the bus swung wildly toward the river, almost spilling over the bank before grinding noisily into reverse, finishing a tight, three-point turn, and rumbling back out onto the road.

Looking toward the nearly impassable road that led to his home, he immediately discarded going home this early. The dense undergrowth and bulky trees cast an almost permanent dark shadow over the road’s gloomy passage, more like a creek bed, washed out and riveted with large rocks that scrapped the bottom of his mom’s car causing her to say, “Shit!” every time they came or went, as if it was unexpected. Two other homes shared the same road, an old man with a grizzled, sway-backed horse as decrepit as he, and a lady and her full-grown son, a no-good, lazy bum, according to Tommy’s mother. Tommy disliked sitting around in the empty house waiting for his mother to come home, even though he mostly felt an uneasy aversion to being there with her as well. Somehow, although she essentially ignored him when she was there, the hollowness inside seemed more amplified when he was home alone.

Peering into the sky through the heavy green tops of massive oaks, Tommy searched for signs of the typical, late afternoon thunderstorm of Indian summer. Deciding that a storm wasn’t coming anytime soon, Tommy wandered down the river bank and stooped in the thick shade. Picking up a knobby stick, he poked around in the loamy dirt, popping up a worm, fingering its thick-muscled body between his fingers. He liked the way the worm didn’t have a noticeable head and wondered if it could slither through the ground the same in either direction. Releasing his wriggling catch, he watched it disappear soundlessly into the rich soil. Tommy stood and moved closer to the rippling river water, tossing a rock into green-blackness, listening to the dense thud that followed the splash, making him wonder what the river would look like underneath if all the water was gone and he could see the river-bottom exposed.

Using his stick to furrow a path along the fringe of the river, Tommy pretended the groove was a train track and imagined the train charging through the rugged countryside, thrilling around the bends of trees and soaring up the hillsides. He contemplated the fearless engineer who knew all the turns of the track, driving the train through many kinds of weather, sounding the horn at every road in every town across miles of land. Pulled out of his reverie when a chunky web of roots gnarled his stick, splattering black, mealy dirt into his face and over his shoulders, he tossed his stick and shook his head, feeling the cool dirt slide under his collar, down his belly and back.

Eyeing the sky again to gage how much time he had before his mother came home, he decided he still had more time and continue to stroll along the river bank, up the steep embankment, over the guardrail, onto the paved, two-lane road and across the bridge to the train tracks. This is where Tommy had spent most of his time for as long as he could remember. He knew every wooden tie, all the joints, each bolted plate, and the shiny surface of the steel tracks for the entire section from the road to about even with where he imagined his house must be on the other side of the river. He couldn’t be sure exactly where his house lined up because summer vegetation and mountainous slopes effectively hid the winding, rutted road of his home.

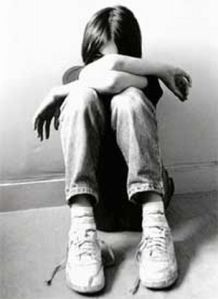

Tommy bent down, perching on the track in a tight, athletic crouch and ran his short, broad fingers across the shiny, worn surface of the tracks, tracing the dents and rust. Sighing sleepily, he relaxed onto his back, centering his body perfectly on a single rail, feeling the warmth of a day’s absorbed sun seep from the steel into his spine and ribs. He closed his eyes against the waning sun, letting his mind wander to what he wondered about most in the world, the thing that constantly tore at him inside, a pain somewhere in his chest that burned and throbbed whenever he stopped moving long enough to feel his body. He pondered the man who somewhere walked this earth, maybe with the same shape eyes, thick blond hair or similar curve of his back. He imagined what this man might be doing at this very moment, what he did for work and who his family might be, what his voice sounded like. He wondered, most excruciating of all, whether this man ever thought about him, Thomas Akin Brown, or whether his mother had ever bothered to let this man know that Tommy existed in the world. As drowsiness overtook him, he settled with the almost physical realization that his mother probably never did tell, didn’t care enough to tell and the underlying, ugly truth was this meant he didn’t matter. His being here was not worth telling.

His soft, anguished breaths became deeper as the sun vanished and the earth’s heat disappeared in the stain of late afternoon. After some time, his chest rhythmically rising and falling, he suddenly startled awake, feeling the river-cold mist chilled in his body. Rising stiffly, he rubbed his burning eyes and squinted into the shadows, feeling confused and disoriented. He stumbled, numb and cold, across the bridge, adjusting slowly to the gray-black shapes blanketing the familiar road and followed the well-known contours by using his eyeless senses, across the rocky river-landing and turning blindly onto the final stretch, feeling the dewy slap and gentle tangle of the crowded foliage on his face, arms and legs, up the worn, porch steps, slipping noiselessly into his dimly lit home.

Tommy’s mother was perpetually irritated at him for reasons that weren’t readily apparent. He was a generally agreeable child, obedient and quiet and this seemed to irk her more than any amount of defiant noise and rebellion. Even more annoying, he was kind-hearted most of the time, tender with and curious about all kinds of nature’s creatures, thoughtfully holding store or restaurant doors open for strangers, purposefully picking up and discarding errant trash while his mother huffed impatiently, aggravated by the interruption. Most school days, when he came in from outside, well after he knew she would have gotten home from work, she would hold him hostage with her accusing inspection and try to find fault with him.

“You should have been doing your homework,” she’d say.

He would meet her eyes, knowing that this too made her mad but unable to stop himself, “Yes Ma’am.”

Sometimes her body’s posture would soften slightly, as if she considered being nurturing but typically lost this notion just as quickly and Tommy knew then that he was already forgotten, a temporary bother she assuaged by calling one of her friends on the phone, stepping outside to have a cigarette or going to her room and closing the door. More times than not, she would have a male visitor who arrived several hours after dark, one more man in a long, boring string of men who would pat him on the head or shadow box with him for an unpleasant two minutes before disappearing onto the back porch or into his mother’s bedroom. Although Tommy hated this, he never talked to his mother about the men and this displeased her as well. She glared at him reproachfully, pinning him with her cool eyes in the front hallway as he tried to escape out the door each morning, “Don’t you look at me like that, young man. You don’t have a clue what it’s like for me. You think you’re better than everybody. You know what you are? I’ll tell you what you are… you’re too big for your own britches.” Tommy learned to escape into his mind when she talked like this because saying something or not saying something had the exact same result. He learned to let her have her say and disappear at the same time, off in his inner world where she couldn’t touch him with her words or her disapproving scowl.

Tommy’s mother was undeniably beautiful, the kind of woman who looked as lovely disheveled in the morning as when she was dressed and painted for a night out. Whenever Tommy would allow himself to acknowledge this, he felt an instantaneous wash of shame, as if her radiance overshadowed his right to be in the world, as if he was an uninvited intruder in her glittery life. Tommy was distressingly aware of the effect his mother had on others, with her brilliant blue eyes, set just-so in her creamy-skinned face and long, dark eyelashes, her stunning blond hair, beautifully shaped body and pink, perfect mouth. He saw the way women’s faces would visibly tighten when his mother was within eyesight of their husbands. He noticed the helpless, admiring eyes of men, fixated on his mother’s every move, attracted to every uttered word. She was steamily alluring and her sensual influence was like a covert drug, softening resolve and blurring commitments.

Tommy’s mother was a waitress, which gave her ample opportunity to capture all the men she desired, and Tommy grimly noted that his mother apparently required a constant variation of male attention. The house-visiting men were rotated regularly by Tommy’s mother but all seemed happy with their own sporadic visits within the constant stream of suitors. Tommy hated everything about this. He found his mother’s appeal mortifying and he pitied and despised the men who were droned into her web. He soothed himself by playing a game of incessant alertness for men who had never met his mother, seeing them as fresh innocents, viewing these men as curious anomalies, pawns who were untouched and unclaimed, reeking with the possible heroism of resisting his mother’s charms. He indulged himself that such a man existed and thinking this thought sometimes was enough to slightly ease his anger, diminish his disgust.

Only once did Tommy try to talk to his mother about his father. He had already learned to calculate her moods, at six years old, and took the chance that this might be one of those amiable moments. She had just washed her hair and was sitting in her purple, silk robe at the kitchen table, mindlessly thumbing through a magazine, cigarette poised in her polished-nail fingers. She smiled absently at him when he sat down opposite her.

“Mom, who is my daddy?”

The smile, still visible on her face, now had a gray-death feel to it, reaching across the table, turning Tommy’s blood to ice. “Your daddy is a no-good bastard and I don’t ever want you asking about him again. Do you understand?” Her words

punched Tommy in the gut as effectively as if she had physically assaulted him. His eyes welled and spilled and she stared at him as if he was as inanimate as the chair in which he sat. He felt as if something inside him balled up and died, smothered alive without any chance of revival. He slid his chair back, watching her impassive face shift into distraction with her nails, examining each tip, admiring its perfection. He got up, trancelike, his stomach lurching, cutting through a cloud of her smoke exhale as he passed her chair, out the door, his head spinning, up the steep stairs to his room. As he lay motionless on his bed, reeling with revulsion and queasiness, he knew without any doubt, but didn’t know how he knew, that she was lying to him. He knew the pathetic truth was that she didn’t know who his father was because she had too many men. Every time since that day, if Tommy would let himself remember, it tasted like vomit.

Occasionally his mother took Tommy to church. Tommy knew these church days were about his mother being seen, coiffed and perfumed, all smiles and implied humility. Still Tommy used to believe, when he was younger, that this might be the one safe place where men could hold their ground against his mother’s temptation. “Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil…” the church members would stand, holding hymnals, vowing in unison. Tommy clung to the words like a sword, a strong protection clasped in his hands until the day when he was eight and he met his mother coming out from the side door of the sanctuary, flushed and fluttery, the married preacher just a couple steps behind her, smiling the dumb smile Tommy had seen splashed on too many men’s faces.

As soon as Tommy sat down in his assigned desk seat at school on Wednesday, he knew something was different. He didn’t smell his teacher’s perfume; the throat-clogging aroma had been a constant in the room since the first day of school. Standing in front of the class with his back to the room was a mysterious man in a grey suit coat, short black hair neatly trimmed to the collar, his long legs strong in his pants. Tommy studied the man’s back, watched the way his muscled shoulders flexed as he wrote on the blackboard, the side of his face, gold rimmed glasses high on his nose, referring to pages in a opened book on the teacher’s desk. Tommy thought he looked powerful and unusual, deciding he was probably not from their town by the way he was dressed, teachers at his school never wore suits.

When the man turned to introduce himself as Mr. Shaw, the substitute who would replace his teacher for at least two months due to illness, Tommy felt his heart pound inexplicably. He pressed his hand to his chest unconsciously and listened as the man began to talk about himself, including how he had journeyed two days ago by train to Georgia from Vermont. Propping a tall, beefy leg over the edge of the teacher’s desk, the teacher smiled warmly, engaging the children with his unhurried manner, answering questions, clasping his hands gently on his lap, letting the children interrupt and share their own stories triggered from what they heard.

He told of growing up in Vermont, helping his grandfather harvest maple syrup and of his first job, working in the copper mines of Tennessee as a young man, how the sulfur runoff caused the land for miles to become bare, red mountains, like Mars. He described the snow in New Hampshire, hanging heavily on pine trees and how he cross-country skied through the magical forests for exercise. He revealed that train transportation was his favorite way to travel, how passenger sleeper cars let you sleep as the train moves across the country, how the dining car serves meals with fine china and real silver salt and pepper shakers.

The children were riveted in their seats, fervently listening, glancing at each other with smiles in their eyes, sharing the moment as if they were getting away with something forbidden, this utter enjoyment of class time, this man who was so foreign and different. Tommy suddenly felt urgently self-conscious. He wanted the teacher to notice him but at the same time felt nervous that he might be seen. Throughout the day, Tommy found it almost painful to look at Mr. Shaw, his confidence such a generous thing, his solid chest visible in his fine-tailored shirt, his impeccable speech irresistible. He exuded a lucidness, an other-worldliness that Tommy could sense as strongly as he smelled his mother’s constant disapproval.

As the day’s morning moved into lunchtime into afternoon, Tommy felt dizzy and wobbly inside, his head detached and oddly distant from his body. He foggily noticed the teacher moving through the aisles of desks, touching shoulders with encouragement, clearing his throat occasionally when a child’s attention wandered, smiling approvingly when the children raised their hands or read from their work. When it was his turn to be touched by Mr. Shaw with a light tap on his shoulder, Tommy felt his body tremble with a queer sensation, a new vibration of being recognized; him the unknown boy in the seat, appreciated by the glorious, new teacher.

School days went by in a blur. Tommy felt euphoric with an unimaginable joy of being, each day sitting in his desk, three rows back from the front, two aisles to the right of the teacher’s desk at the front. He had learned the pattern by heart, Mr. Shaw’s morning stories and sharing, standing at the blackboard, drawing and writing, captivating the students in some new lesson, his broad, handsome smile touching each face as if his attention was a ray of light straight from the sun’s core. Mr. Shaw’s magnetism was enormous, the movement of his hands as he spoke, the poise of his confident man-stance. Observing his teacher’s hands, Tommy could not imagine this man’s arms around his mother’s waist, this man’s hands grabbing his mother’s hips as the men who intruded his house. Tommy could not fathom this man appearing after dark and disappearing like a coward before dawn.

Tommy felt a buzz of anticipation as Mr. Shaw strode his daily rounds of the classroom, cultivating, inspiring, supportive in words and touch, connecting and impressing a gift of appreciation for each child, each unique personality. As the days grew into weeks, Tommy’s confidence bloomed, he began to feel lavishly noticed and regarded. Each exchange with Mr. Shaw was like honey-water to his soul, quenching a thirst he had not known was there, relieving the emptiness of a void unnamed. Tommy felt an unusual eagerness to please, a desire for involvement, in a way he had never expected.

Going home each day, however, Tommy would fall into a sodden despair, heavy with fear, holding his breath unconsciously. Each day the dreaded knowing grew, the assurance that his mother would eventually find out, would notice a different lightness in his being, would resent him for it and pry into its cause, would find out from someone in town, her customers, about this marvelous new man, a promising, untouched-by-Tommy’s-mother phenomena. Tossing restlessly at night, Tommy knew that when this happened, the certainty of which he did not deny, his sublime dream would come to a snapping end, crushing his heart and ending his hope in an instant.

Five weeks into his new teacher’s employment, Tommy suddenly felt as if a dam had burst inside of him. All the anxiety of worrying that his mother would taint and ruin this last, pristine man with the lure of her attractiveness had finally reached a crescendo. Riding home on the bus, Tommy felt weepy and despondent. It was as if a lever inside him had turned and a scalding, liquid movement was filling his inner cavity. Disembarking from the bus, the river looked dim and somber to Tommy. The trees felt lifeless and obscure. Tommy sat on the bank of the river for a while, feeling his body hum with some unknown yearning, an unspeakable misery. As he watched the familiar rippling of the water, his eyes stung with grief, the depth of which he had no understanding but felt as a relentless picking and plucking within his belly.

Straightening up stiffly, bewildered at his heavy melancholy, Tommy walked across the bridge to the familiar railroad track on the other side, followed the steel rails of the railroad with his eyes around the corner, deep into the green foliage until it disappeared. He imagined the place called Vermont, his teacher riding the train across mountains, over bridges similar to this one, his teacher sitting with his face near the sun-warmed windows, seeing the beauty of Georgia unfold as he neared the station. He imagined Mr. Shaw selecting him, Tommy, as his favorite student, the most beloved child in his class, lavishing him with praise and adoration that had no bounds, no expectations. He felt the wonder of envisioning such a benevolent focus of a person towards him, the possibility that he could be important enough for someone to regard him with kindness and unselfish commitment.

Tommy lay down on the single rail as he always did, contemplating the yellow-gray sky through his half-closed eyes. The steel felt cold and unyielding between his shoulder blades, his body turning numb except for a dull ache in his chest. As he reflected on all his teacher had said, his movements, his presence, Tommy imagined the rhythmic vibrations of the train that had brought this teacher to him and, just as abruptly, realized with a throbbing dismay that his teacher’s impending final day, probably just three weeks away, would mark the end of the solace Tommy found in him, with or without his mother’s involvement. Either way, Tommy understood with a shudder, his life was doomed, his teacher would ultimately depart from his life forever.

As darkness spread across the river valley, Tommy suddenly felt aware of the time and vaguely realized he was hungry. Entering the front hall of his home, he could hear his mother talking on the phone in the living room. He pictured her in her usual place on the end of the sofa, one arm hanging over an ashtray on the floor, one leg propped up on the coffee table, her head cocked toward the armrest.

“Really? I’ll have to ask Tommy. I didn’t know. What? He came on the train from Vermont? Over a month ago? I don’t understand why Tommy hasn’t said anything about him.”

Tommy could hear her take a long drag from her cigarette as he stood in the shadow of the hallway, invisible to her.

“I know… He’s probably some loser who ran out on his family like all the other losers.”

Tommy moved closer to the stairs, his hand on the banister.

“Tommy, is that you?”

He ignored her and ascended the stairs, his stomach twisted and repulsed, his room first on the left, a cluttered storage room on the right and an uninspired, yellow-sunflower guest room at the end of the narrow hall, never used, collecting spider webs and dust. Flopping on his bed, not bothering to turn on the lamp, his body felt weightless, as if a big chunk of matter had flown away from him and nested somewhere on the roof, bathing in the moonlight, unseen and unremembered by the world. As he laid there, his body barren, his eyes fixed and glazed, his mind grappled with the insight that hope could be such a solid thing and now was flung from him, leaving him split-opened and abandoned. He could hear his mother talk well into the night, interrupted by slams of the screened-in porch and the car that arrived, her raspy, smoker’s cough, a strange man’s voice echoing through the floor beneath his bed.

Read Full Post »